Reconstructing Yuanmingyuan: confronting colonial history through recreated images

A conversation with photographer Shi Yangkun on the role of photography in colonial expansion and how his work aims to subvert it.

Hi there,

This is Charlotte. This week, I’m temporarily taking over Far & Near to write about something I’ve been researching and thinking about for a while: colonialism and its entanglement with the history of photography, with an extended conversation with artist Shi Yangkun on his recent work reconstructing the images of Yuanmingyuan — the predominant symbol of foreign colonial aggression in China.

Far & Near is a completely independent, reader-funded, paywall-free newsletter. If you like our work, please consider a paid subscription and help us do more work like this.

Your support is critical to the sustainability of this newsletter.

Located on the northwestern outskirts of Beijing, Yuanmingyuan, or the Garden of Perfect Brightness, was once the world’s most extravagant imperial palace. Five Qing emperors filled the palace with their most prized artworks and processions, and its sprawling complex comprised several royal residences, gardens, temples, and libraries. When British and French troops waging the Second Opium War on China arrived at Yuanmingyuan in 1860, a crazed plunder ensued. After the looting was over, four thousand British troops were ordered to set Yuanmingyuan ablaze, and the fires burnt for three days as the vast complex was reduced to ruins.

For decades following its destruction, the Chinese had trouble piecing together what Yuanmingyuan looked like. “Forty Views of Yuanmingyuan”, a series of paintings commissioned by Emperor Qianlong to capture the imperial palace’s splendor (and the only surviving records of what sections of the palace looked like), was taken by French troops. The paintings eventually ended up in the National Library in Paris. They are still there today.

The two Opium Wars, ending with the desecration of Yuanmingyuan, were the beginning of a "scramble for China, " involving several western nations and Japan. These events unfolded against the backdrop of Europe’s global colonial expansion, which reached an all-time high at the turn of the 20th century. By 1914, Europeans had conquered or colonized more than 80% of the entire world. It was during the height of European colonialism that photography was born and popularized throughout the world, often following the steps of colonizers, explorers, and traders.

When I moved to Berlin a few years ago, I started researching the history of German colonialism in my hometown Qingdao—and by extension the legacies of European colonialism in China and the world. I often struggled to find the right words to express my thoughts when confronted with the brutal details of colonial history, the often dehumanizing colonial perspectives that still define how many parts of the world are seen today, and also the fact that the history of foreign subjugation in China is sometimes co-opted into nationalism-promoting propaganda. (The ruins of Yuanmingyuan, for example, have been propelled into a symbol of national humiliation and a site of nationalist education today.)

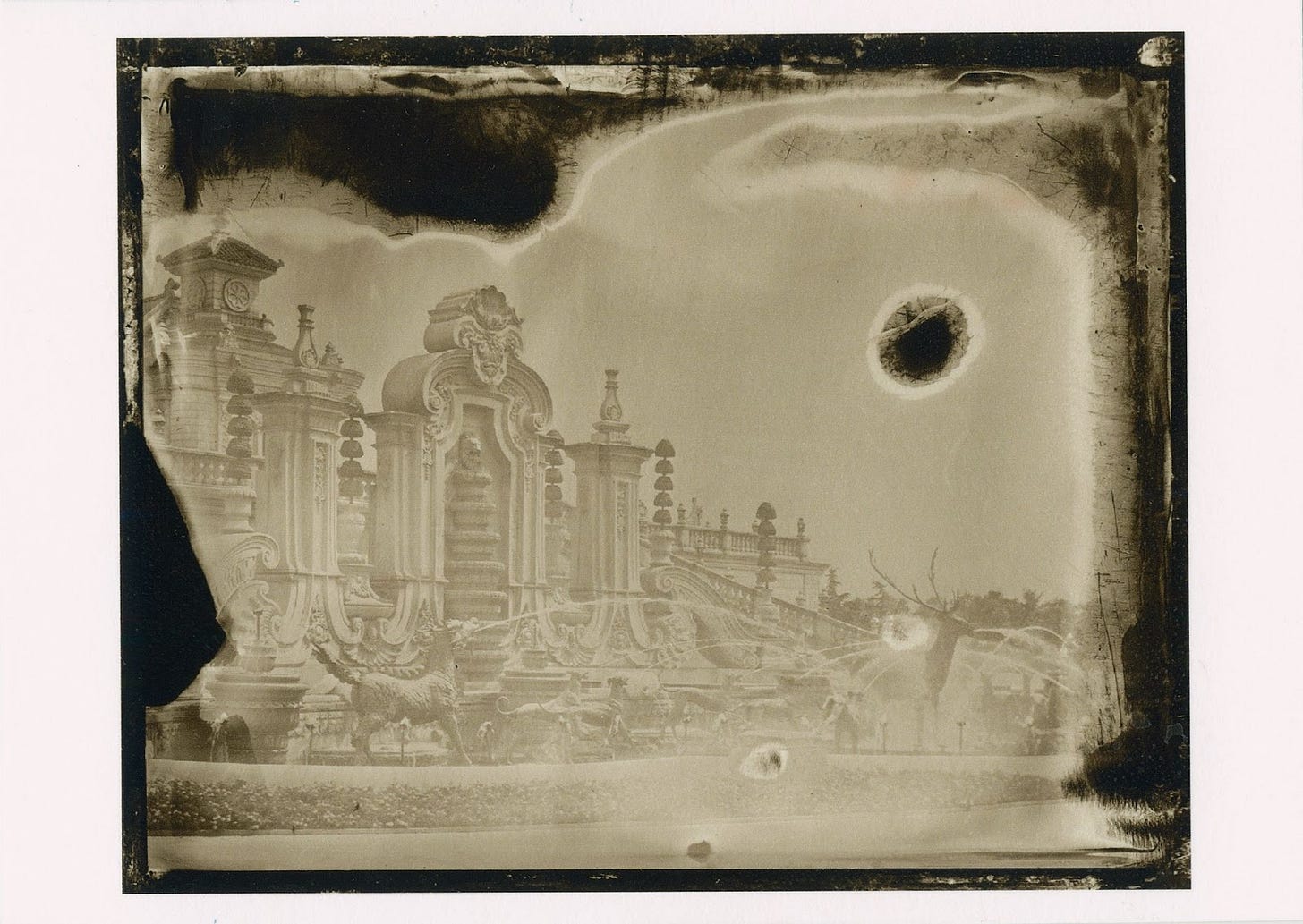

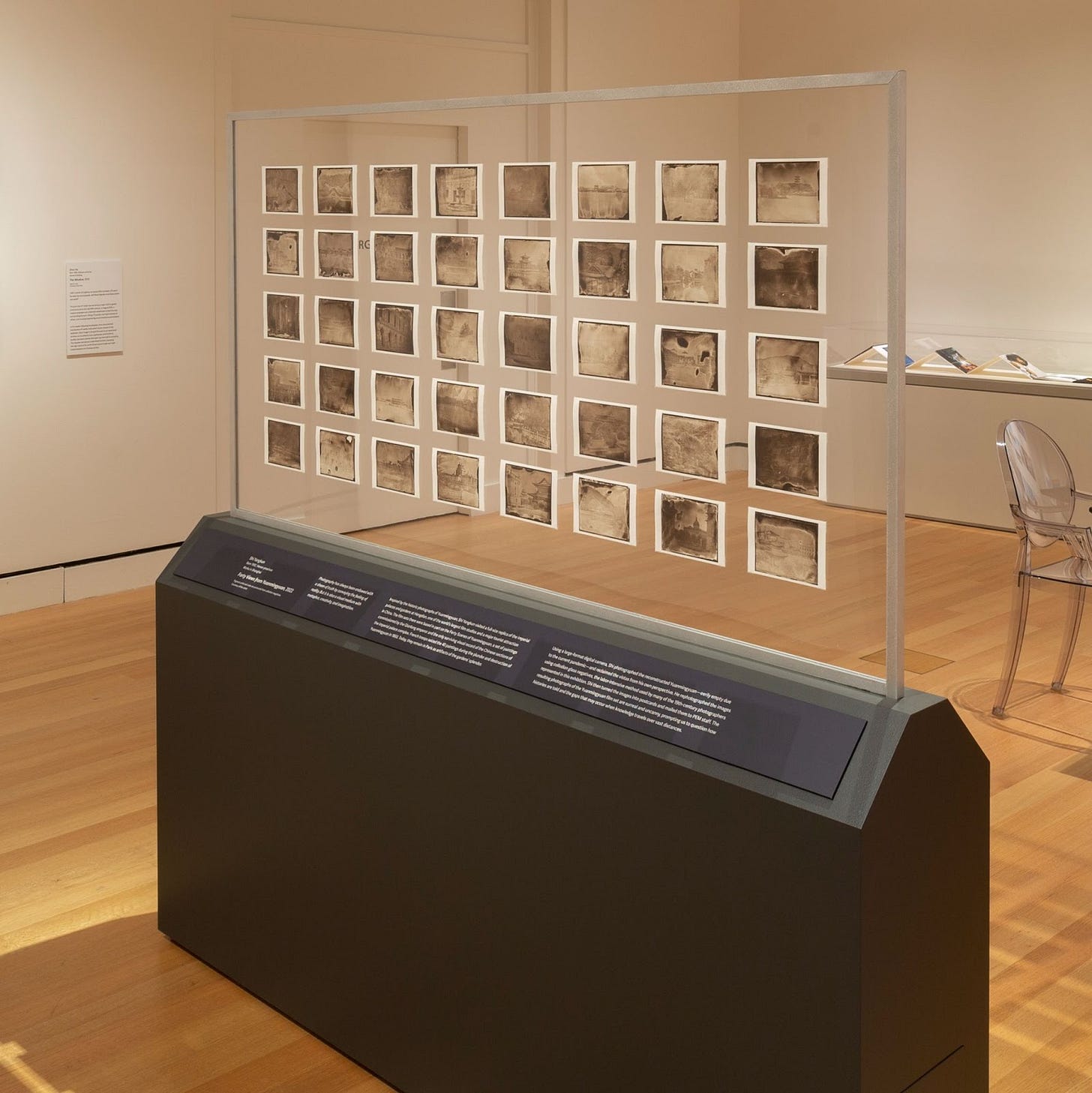

That’s why I was glad to see Shi Yangkun’s photography series, “Forty Views of Yuanmingyuan”, inspired by and titled after the lost palace paintings. Using digital photography as well as wet plates, a 19th-century photographic technique, he reproduced what Yuanmingyuan looked like and reprinted them on postcards. The work was created for “Power and Perspective: Early Photography in China”, a current exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum in Salem, Massachusetts, United States. The exhibition, featuring images captured by foreign photographers as well as Chinese ones at the time, explores the role of the camera as a colonial, military weapon that moved across China and selectively depicted the country. It runs until April 2.

I exchanged emails with Yangkun to talk about the colonial legacy of photography, how he recreated the scenes of Yuanmingyuan (hint: with the help of China's largest film studio), and how one might participate in post-colonial discourse as a Chinese artist. The interview was translated from Chinese and edited for clarity and brevity.

A symbol of western colonial aggression

Charlotte: Your project, Forty Views of Yuanmingyuan, is a part of an exhibition that explores the colonial and imperial legacy of photography. How was China typically depicted in early photographic images?

Yangkun: When PEM commissioned me to create this work, I was granted access to the museum’s photo archive. I saw a lot of photos of China in the 19th century and wanted to know about the history behind it. These collections were mostly taken by foreign photographers who crossed into Chinese territories by embedding themselves in military incursions or traveling here to seek the exotic.

Many of the photos were taken by Italian–British photographer Felice Beato. Beato started photographing wars and ruins in the mid-1850s. He photographed the Crimean War in 1855 and subsequently traveled to India to photograph the Indian Rebellion. In the later stages of the Second Opium War, he was embedded with British troops and captured many images, including the ones of Yuanmingyuan before and after its destruction. I later learned that the PEM Museum holds one of the largest collection of Beato’s China photos in the world (85 photos).

Beato used collodion wet plates, an early photographic method commonly used in the 19th century. The photographer would get a negative image on a glass plate with this process. Beato would take the wet plates back to London and print them on albumen paper to produce postcards and photo albums for sale. This is why I chose wet plates for my project and reproduced them as postcards.

Charlotte: How did you choose Yuanmingyuan as the subject for your project?

Yangkun: I happened to be in Beijing when I was researching Beato’s photography. His architecture and landscape photos of Yuanmingyuan and other imperial gardens piqued my interest. So I took a trip to Yuanmingyuan and got really drawn to the relics. I know the burning of Yuanmingyuan was a symbol of the Century of Humiliation in China from my elementary school history classes. I thought of photographing the ruins of the real Yuanmingyuan in Beijing, but that was too direct for me.

Charlotte: What do you mean by direct?

Yangkun: I think making art is a constant process of translation. The key is to visualize complex text and objects. The ruins of Yuanmingyuan itself and the history it carries are too heavy and too symbolic. If I just photographed the ruins and sent them to PEM , it may feel like an indictment, which is not the direction I want to go.

Recreating Yuanmingyuan

Charlotte: You went to great lengths to show what Yuanmingyuan looked like. First you went to Hengdian, the largest film studio in China, where there’s a reconstruction of the Yuanmingyuan.

Yangkun: Hengdian is dubbed the Hollywood of China. Many TV series and films are shot here. A lot of young aspiring actors live here, playing extras and picking up odd jobs. I carried a lot of equipment and after two days in scorching heat, I found a “Hengdian drifter” to help me. He thinks the Yuanmingyuan replica is quite grand. Every day we met people dressed in historical costumes or wedding gowns posing for photos on the set.

I had mixed feelings. This full-size replica is the result of a huge investment but it looks very cheap. But many historical dramas and movies are made in Hengdian and formed our visual understanding of history. My wet plates pictures are also cheap remakes of what the original paintings could have shown. I wanted to use "fake" images to retell "real" events.

I stayed in Hengdian for about 20 days, shooting the replica with a digital camera. Using wet plates directly would have been too expensive for me. I’d have needed a makeshift darkroom. Back in Shanghai, where I did have access to a darkroom, I printed these 40 photos in my studio and then recaptured them using wet plates. It was like a remake of a remake, a process of reproducing a fake image.

Charlotte: Why did you print them as postcards and mail each one to individual museum staff?

Yangkun: I wanted to reference 19th-century postcard culture. Beato and other photographers like him took photos of China and sold them as postcards that were full of imagination of “the exotic.” On my postcards, I wrote nothing other than the addresses and names of the PEM staff. Museums are spaces of power, and I hope to “touch” the real people who work there. By the way, when I was creating this work, Shanghai had just re-opened after a long lockdown. Besides the postal stamps, there are also “disinfected” stamps on the postcards. For me, this stamp is also a symbol of the history I’m experiencing right now.

Chinese artists in the postcolonial discourse

Charlotte: The project was specifically commissioned by PEM as a response to early images of foreign photographers in China. What did you hope to achieve through this project by itself, and in relation to their works?

Yangkun: I’m very grateful to PEM for this commission because my work and the works of several other young Chinese photographers are included in the last exhibit room. Without this part, it would have been difficult to claim that the exhibition was presenting a “decolonial” perspective. The intention of my project is exactly to respond to the historic photographs exhibited in the previous exhibit rooms from my perspective as a young Chinese artist.

Museums represent the power of narrating histories in certain ways and presenting them as the truth. If an American visitor walks into this exhibition, they may mistake my photos for real images of Yuanmingyuan before its destruction. I want my work to give the viewers a pause. Maybe that’ll help them reflect on everything they have already seen and ask whether those pictures are reliable depictions of history.

Charlotte: Because of this history of being colonized, is it a given to say that Chinese artists have an inherently anti-colonial perspective?

Yangkun: I don't think contemporary Chinese photographers necessarily have an anti-colonial perspective. Anti-colonial perspectives must be obtained by reflecting on power. Some photographers may not realize that when they pick up a camera to photograph others, it is an enactment of power in itself. For example, a young Chinese photographer travels through Liangshan (where the Yi minority group lives), takes images of poor children, and uploads them online. He may get millions of traffic through the images of others’ suffering, without having reflected on the exploitative nature of this way of looking. It is from a position of power that is to some extent similar to the colonial gaze we are discussing.

Charlotte: This history of foreign subjugation is considered a dark period for China and is sometimes entangled with nationalism. Has working on this project offered you any new understanding of that part of history?

Yangkun: I was actually not that familiar with the history of colonialism in China in the 19th and early 20th centuries. I felt what I learned in school was tinted with nationalism and patriotism. I realized later that “history” is very similar to photography, in the sense that they both look real, but we can never reach the truth through it. So as a Chinese artist, I wanted to use this commission as an opportunity to delve deeper into that history.

Charlotte: Postcolonialism is increasingly becoming part of the conversation in the art world. How do you think Chinese artists can participate in this conversation?

Yangkun: Western curators and museums have for a long time looked at Chinese artists with a colonial gaze. This may still exist today but hopefully it’ll be reduced by all the postcolonial discussions we have today. As an artist, I want to use my experiences and thoughts as an entry point to join this conversation with honesty and sincerity. In the collaboration with PEM, we have a shared value—decolonization. The museum hopes the exhibition can take on decolonial values and reflect on colonial history. This is also what I want my work to touch on. The conversation starts with a shared value.

About the artist:

Born in 1992, Henan province, China, Shi Yangkun uses the language of photography to explore the complexity of Chinese society in a subtle way. His work has been exhibited nationally and internationally in various art institutions, including the Peabody Essex Museum, Shanghai Center of Photography, Zhejiang Art Museum, and Art Museum of Guangzhou Academy of Fine Art. His production has received many awards including the PHMuseum Photography Grant, PDN Emerging Photographer, TOP20 Chinese Contemporary Photographer and the First Prize of UrbanPhotoFest Open.

See more of his work here.

Who we are:

Ye Charlotte Ming is a journalist and visual editor covering stories about culture, history, and identity. She’s based in Berlin and working on a book about her hometown’s German colonial past.

Beimeng Fu is a video journalist based in Shanghai. She is a lover of languages and documentaries.

Yan Cong is formerly a photojournalist currently pursuing a research MA in new media and digital culture in Amsterdam.

Interviewer: Ye Charlotte Ming; Translator/Editor: Beimeng Fu, Yan Cong; Copy editor: Krish Raghav

If you like this post, please share it with others and consider becoming a paying member.

If you’d like to make a one-time donation, click here:

I like those photographs