Preserving ‘community fire’ in the age of e-commerce

Artist Zhang Xiao on his book documenting the transformation of a millennia-old tradition

Hi everyone,

It’s Charlotte here. This February, I went back to China for the Lunar New Year. The last time I was back for the holiday was before the pandemic, and I was determined to have a celebration that’d make up for the ones I missed.

I scoured Dianping and Xiaohongshu for things to do and food to try, because well, I was out of sync with what’s cool yet didn’t want to settle for the mega-malls that’ve come to dominate Chinese city life. This turned me into a tourist in my own hometown, as I followed the trail of glowing reviews to the next “hidden gem” restaurant swarmed by out-of-towners in the summer (It’s hit and miss).

To have the best “niánwèi (年味),” or “Lunar New Year feels,” I turned to the apps as well. A Xiaohongshu search about festive activities filled my screen with lanterns and dragon dances, alongside street snacks branded as "National Intangible Cultural Heritage." Yet, moving from the apps to the real world, I was disappointed to find that every food stall at the New Year street fairs sold the same type of sweet pear soup, and the calligraphy couplets were not handwritten but wholesale items from Pinduoduo.

During this time, I’ve also come across many online and print articles featuring Zhang Xiao’s photographs from Shèhuǒ (社火), or Community Fire, which were published as a photobook last year by Aperture and the Peabody Museum Press.

Shehuo is a thousand-year-old tradition from rural northern China usually celebrated around the Chinese New Year, with performances of folktales in the forms of dance, music, acrobatics and martial arts. You can get an idea of the celebration from this YouTube video:

The vibrant costumes and bustling crowds are the perfect “New Year feels”. Thanks to it now being recognized as an intangible cultural heritage and the promotion on apps like Xiaohongshu or Douyin, this millennia-old practice is now known nationwide.

As a painfully bureaucratic commentary on The Paper states: “The phenomenon of the post-2000 generation re-igniting folk activities has prompted local authorities to recognize the positive role played by short videos and live streaming, and to leverage the creativity of young people to greatly enhance cultural revitalization efforts.”

But to the artist who captured the images, Shehuo’s story goes beyond folk culture being cool again. It's a story that's as much about how the modern world is changing traditions as about keeping them alive. I caught up with Zhang Xiao last month to discuss the preservation of Shehuo in the internet age, the village that monopolized its costume production, and his exploration into the different perceptions of beauty in rural and urban China. Our interview has been translated from Chinese and edited for brevity and clarity.

Far & Near is a completely independent and reader-funded newsletter. If you like our work, please consider a paid subscription and help us do more work like this.

Your support is critical to the sustainability of this newsletter.

Charlotte: How did you come across Shehuo and decide to photograph it?

Xiao: I first photographed Shehuo in 2007. At the time, I had worked as a photojournalist for a newspaper for two years and had started to feel restricted by the job—I wanted to spend a longer period working on a project, but I couldn’t. So I took the Spring Festival holiday as a chance to visit several villages in northern Shaanxi. Shehuo is a well-known ritual in the region and has been documented by a lot of photographers.

I spent 10 days there and realized that I was most interested in the performers and how they were ordinary migrant workers in cities for the rest of the year and then transformed into almost god-like figures back in their hometowns for these Spring Festival performances.

Originally, Shehuo is a ritual where people pray for happiness, prosperity, and abundant harvests. It is rooted in the celebration of land and agricultural prosperity. But now, the meaning of the ritual has shifted, and that’s what I wanted to photograph. The younger generation is less connected to agricultural life, so it’s more about having fun. Especially with the rise of short video platforms, the emphasis on entertainment has grown even more.

No escape from Taobao

Charlotte: Why did you spend so many years documenting it?

Xiao: Actually, after that trip in 2007, I didn’t revisit the story until 2018, when Professor Ou Ning nominated me for the Robert Gardner Scholarship at Harvard’s Peabody Museum of Archeology and Ethnology. The fellowship asked for a proposal focusing on the life of a specific community anywhere in the world, so I decided to go back and photograph Shehuo again.

While I was writing the proposal, I looked up Shehuo on Taobao to see what new styles of costumes and props they were using then.

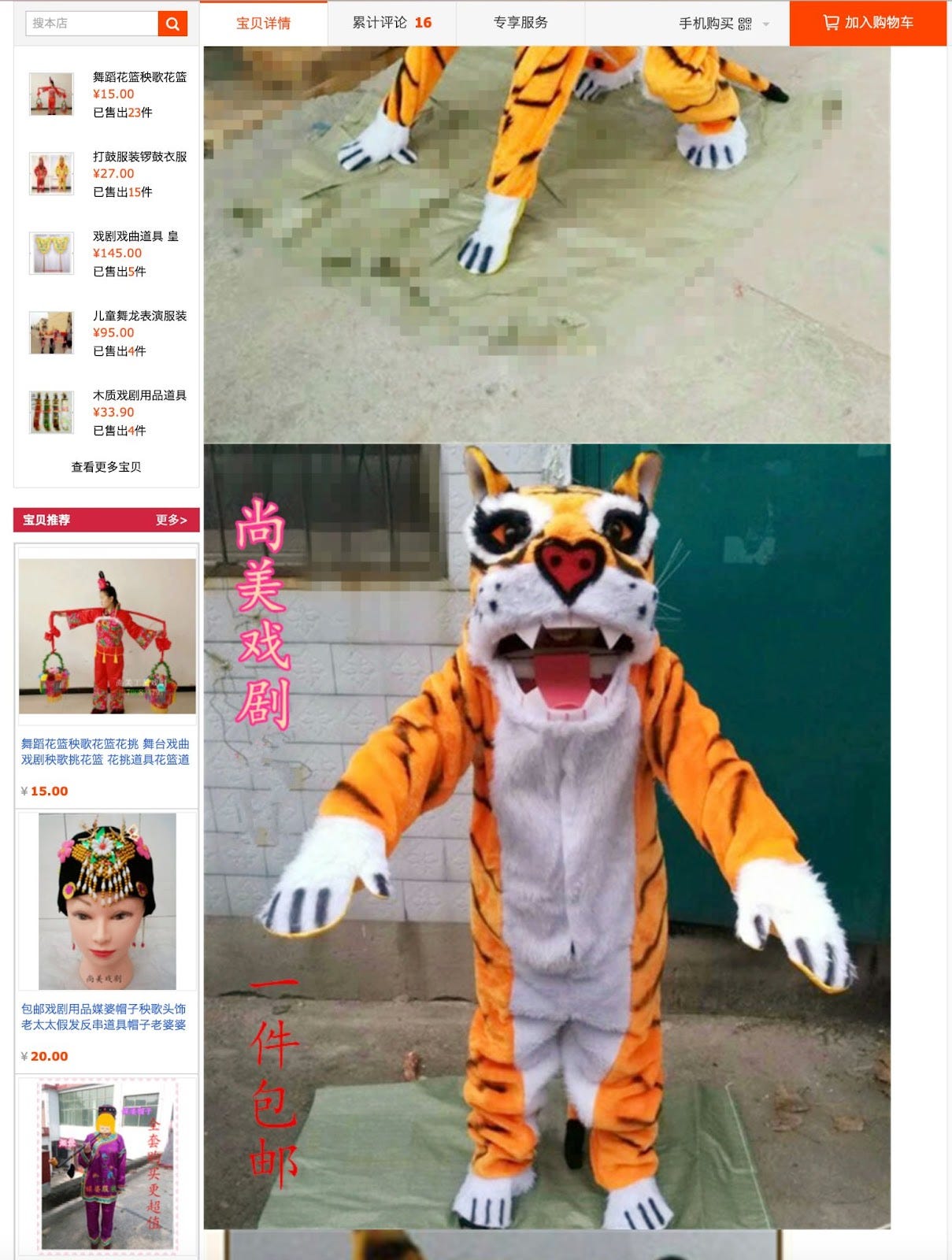

It turned out that most of the products were being shipped from a village in Henan Province called Huozhuang. Almost every household in that village produces Shehuo costumes and props. Traditionally, it was craftsmanship passing from masters to apprentices. But now, not only have traditions changed, their products have also evolved from delicate handcrafts to fast-moving consumer goods.

“Two Ghosts Wrestle”

Charlotte: Is there a big change in how the costumes look now compared to before?