Han Lilin: “Outrage is fueling my creativity, nonstop”

Issue #23: Chinese independent artist on woodcuts, feminism, and learning to speak out in turbulent times.

Hi! It’s Beimeng.

Stepping into Lilin’s woodcut workshop for the first time was a moment of joyous disbelief.

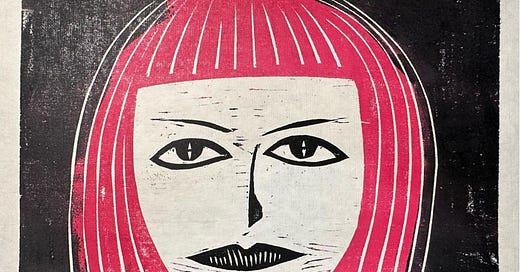

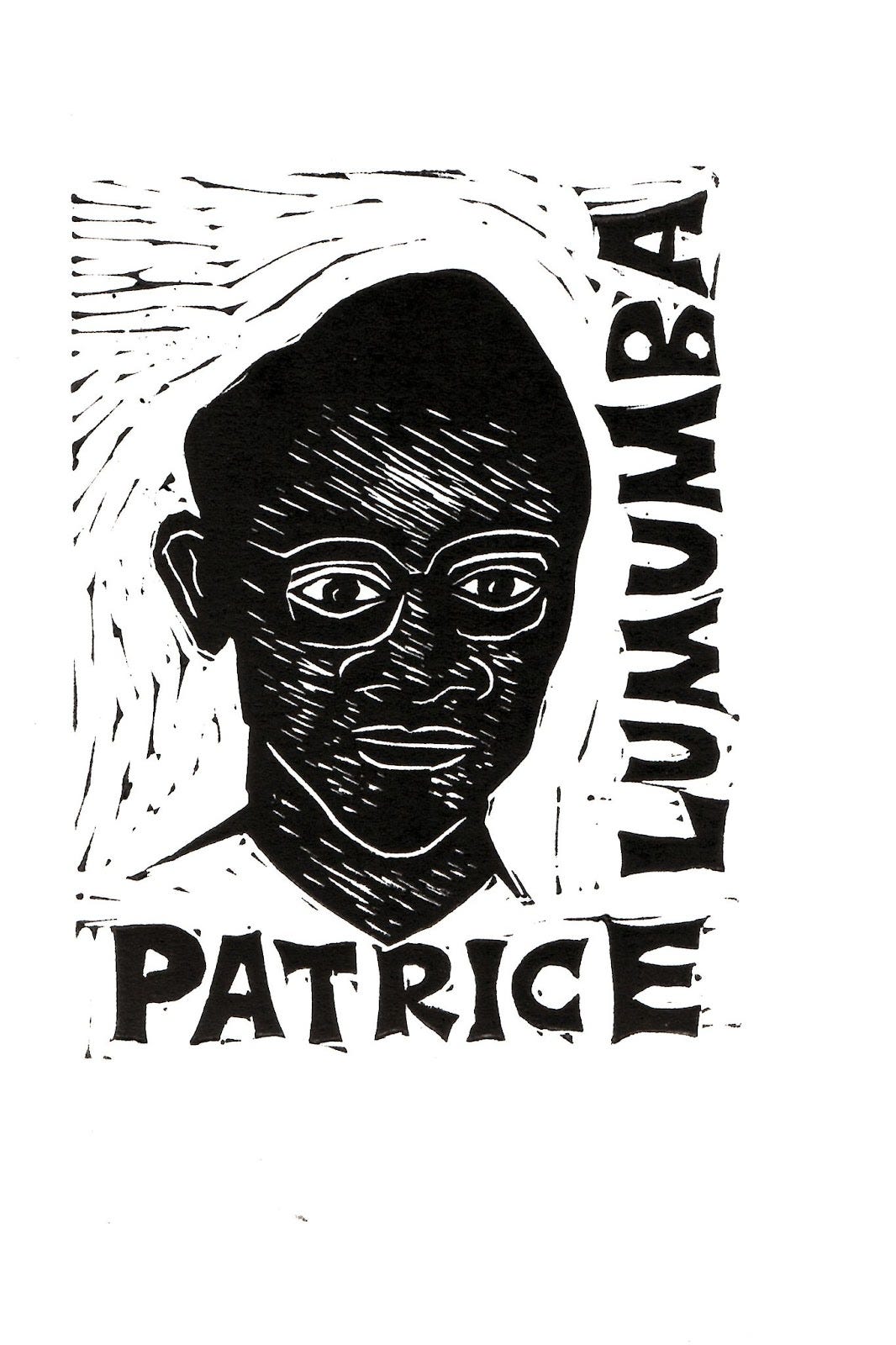

Her rented space on the second floor of an old lane house in Shanghai’s Former French Concession, accessed through creaking wooden stairs, was perfectly preserved in its original form, complete with shared kitchens and separate meters for gas use between neighbors. The walls were covered in woodcut prints, mostly black and white. Made by her and her friends, some feature overlooked historical figures such as the 19th-century Japanese anarcha-feminist journalist Kanno Sugako, or contain provocative statements (“One is never too old to masturbate 活到老,搓到老”). Others are impressive original works addressing current social issues like labor rights, marginal communities, the “chained woman” (see issue #7) and zero-covid experiences.

The disbelief comes from seeing all this in Shanghai, a city that blunts its edge with a distant penchant for self-preservation. Being outspoken is a rarity here. But Lilin, a self-taught socially conscious artist, has managed to form a small community through organizing woodcut workshops where she passes on her skills to anyone with something to say.

Her prints are sharp, the messages simple and straightforward. By keeping a relatively low profile, Lilin defines “impact” in her own unique way.

Before moving to Shanghai, Lilin was the center of cultural and art scenes in her hometown of Dalian. As the owner of Echo Bookstore 回声书店. She frequently hosted live concerts, saloons, book talks with authors like A-yi and Liang Hong, and documentary screenings with Wu Wenguang and Ma Li.

I spoke with Lilin about her journey through these worlds. Our conversation touches on the intricacies of running independent bookstores in China, the unique quality of woodcuts as a medium, her sources of inspiration, and how she channels anger into art. The interview has been edited for brevity and clarity.

Far & Near is a completely independent and paywall-free newsletter. Currently, only 1.5% of our readers are paying members. With your help, we can continue to produce high-quality stories that celebrate the creativity within China and share remarkable human-centric narratives that often go unnoticed.

Beimeng: A lot of things you’ve worked on seem interconnected. They feel like either means of public expression, or gatherings of energy. To start, can you tell me about how you came up with the idea to open up a bookstore in Dalian.

Lilin: I didn’t have a plan for what kind of artist I wanted to be. The workshops I run today are down-sized versions of my previous operations. I ran bookstores in Dalian between 2008 and 2017. Before that I was working in my family business, which got me depressed. So I opened my first bookstore, almost as an act of self-help. My bookstore partner studied art history, and we organized all sorts of events. When we were at our prosperous peak, I had a store on the Dalian beach, and a library near a few universities. There was an exhibition space and a screening room with 24 seats, and every day we played four to five classic films, all bootlegs. It was always with friends that I decided on what kind of books to sell, or what kind of activities to organize. Then a community would gather, and further influence these decisions.

When we screened independent filmmaker Ma Li’s Inmates, over a hundred people came. I was so happy because it felt like a gathering of everyone in Dalian who loved independent films. Afterwards I was smoking a cigarette with Ma Li on the beach, and her eyes were glowing with excitement. The synergy with the community was incredibly powerful, and we gave each other strength.

Sorry if I’m not being humble, but I became the main organizer behind the cultural life of young people there. My interests are wide-ranging—literature, music, movies, contemporary art—I was very aware that there weren’t that many creative people living in Dalian, and I needed to ignite that by inviting people to be there.

But as time went on, the economic pressure became overwhelming, and I had to do all kinds of money-making ventures that actually prevented me from meeting the readers. The number of events I genuinely wanted to organize—and was interested in—also dwindled.

Beimeng: So what happened?

Lilin: The enthusiasm changed. After 2014, I lost hope. I couldn’t sell the books I wanted to sell, which made me feel disheartened and bored. But I continued to push for higher turnover, even resorting to opening up a restaurant in the bookstore. At one point, 90% of my energy was spent on that. Then, I made a 180-degree U-turn. I closed down everything. On the very last day of the bookstore, we all hugged and cried, saying goodbye to the space.

Now I find a lot of joy in making art. It’s so much fun. I am a novice artist, and the scale of my art practice and my approach is very much like someone who just graduated from art college. But I am fine with it because there isn’t a particular mold I want to fit in. I’ve also come to realize that my previous experiences were not in vain and have provided me with a wealth of materials to work with.

Beimeng: Right. If life’s all smooth sailing, then there would be nothing for us to create from.

Lilin: Yes. Honestly it’s only in the past two to three years that I discovered my ability to create art. After my experience with the bookstores, I thought I could become a professional writer, thinking it’d be a familiar way to create meaningful work. I even went to London to take some creative writing classes. However, I soon realized how painful the writing process was, how limited my writing subjects were, because I couldn’t break free from my emotions about the end of my marriage, which lasted 9 years.

I didn't think woodcuts would become a very important medium for me in the beginning. I just played around with it. I got a chisel, a wood board, and just started cutting. It was an instant liberation for me, especially as a left-handed person, as it allowed me to use my left hand creatively for the first time. It seems to do its own thing, almost without conscious thought.

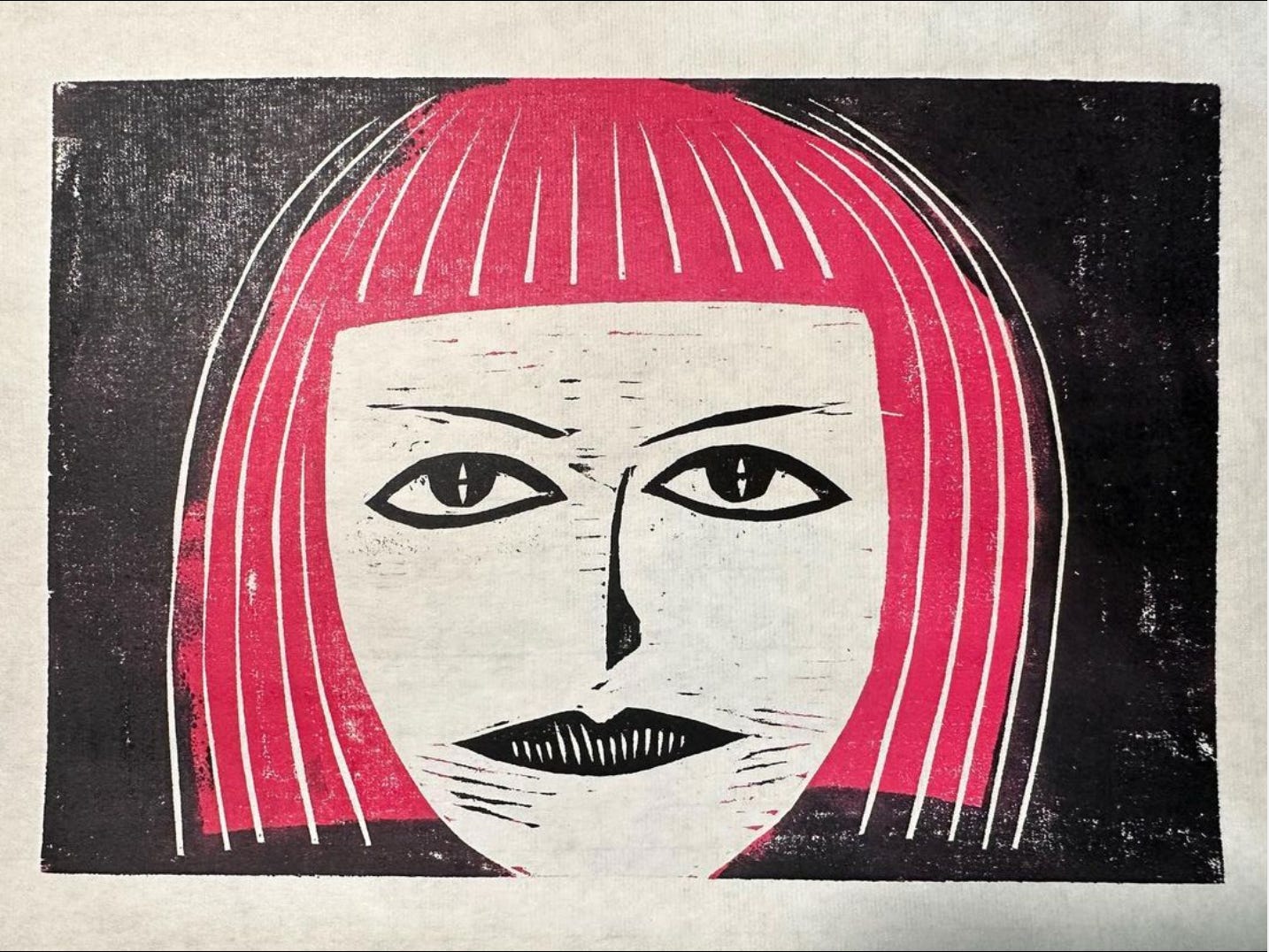

At that time, a friend of mine began putting together the Chinese version of the book “Working Class History: Everyday Acts of Resistance & Rebellion”, and invited hundreds of friends to help translate the work. I translated the part about Patrice Émery Lumumba (note: a Congolese independence leader executed in 1961 in circumstances abetted by colonial Belgium). The events infuriated me. And then I looked him up online, and found him to be a nice-looking man (laughs). So I made a woodcut based on his portrait. My friend liked it a lot, and encouraged me to make more. It’s such an inspirational book about fighting and struggling. Every day I opened the book, got outraged, and started carving. Making art for my friends was the starting point for my woodcut career.

Beimeng: When you first saw the photo of Lumumba, how did you go about carving it?

Lilin: Everyone can create something with woodcut prints, which is the magic of this medium. When I tried it for the first time, I was amazed by how easy and versatile the material was. Being someone who loves organizing events, I immediately adopted it and began organizing workshops in Dalian. Now, here in Shanghai, when people come to my workshop to give it a try, you will see a variety of styles, each piece beautiful and telling its own unique story. It truly is an accessible material, a tool that empowers people.

Beimeng: That sounds fun.

Lilin: With drawing or painting, when you make one stroke, you may feel it’s not enough. You’ll feel it’s necessary to draw a circle. But with woodcut prints, it’s the opposite. The less you carve, the fuller the print appears. This process of transferring the design from the woodblock to paper adds tremendous intensity to the artwork. Just one tap on the woodblock, it becomes a raindrop in a dark night after you transfer it onto paper.

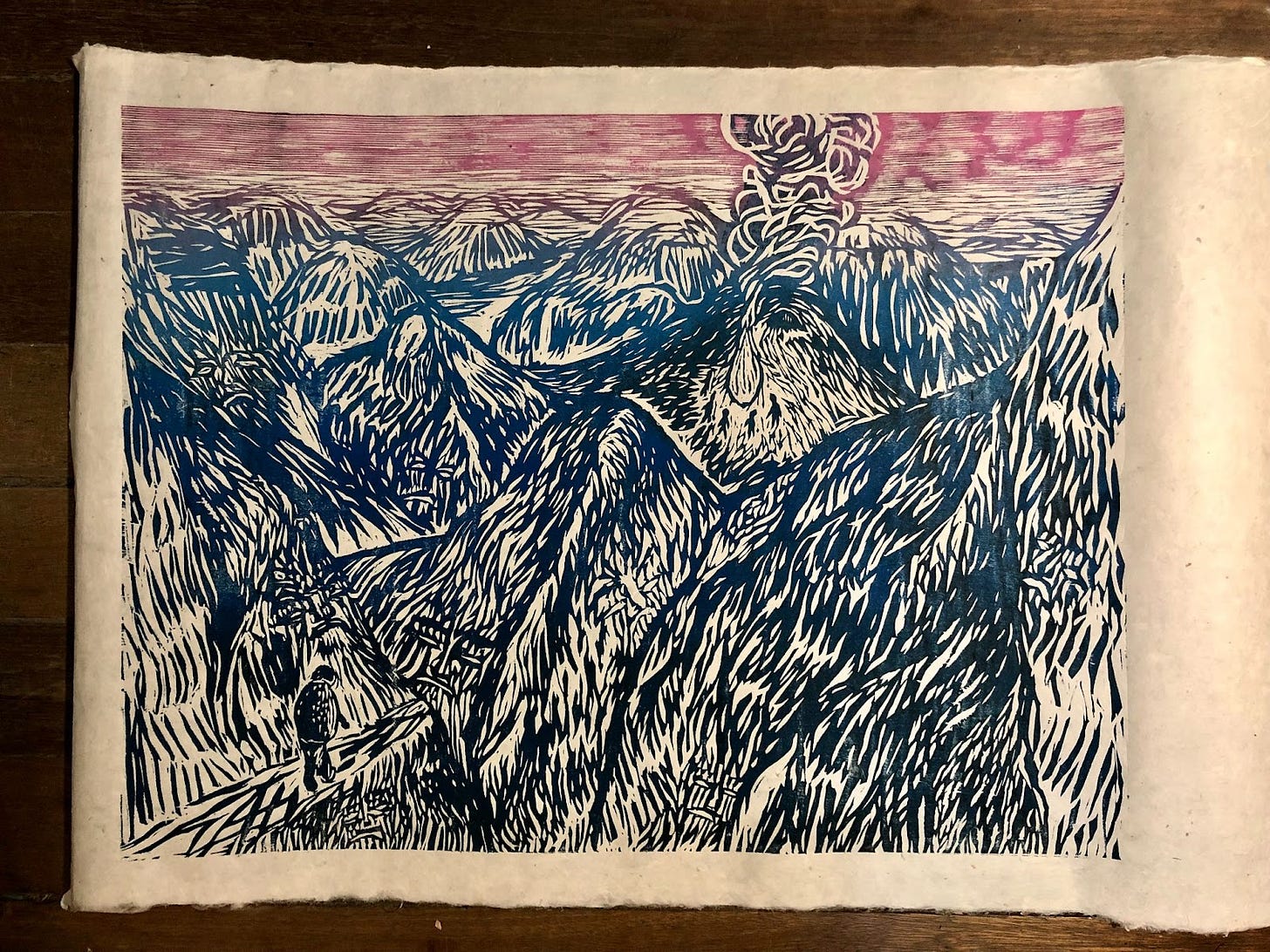

I made a cover for a novel about witchcraft and rebellion set during the civil war in Liangshan Yi Autonomous Prefecture, which tells the story of women in poverty. The novel activated lots of imagery in my mind. I did a few drafts while reading, but ultimately I knew I wanted rows and rows of mountains with vague faces and a bonfire.

Beimeng: Many people are not comfortable dealing with anger.

Lilin: Really? For me, my anger not only gets taken care of via woodcuts, but gets utilized fully. So many anger-inducing things are fueling my creativity, nonstop.

Some people say my work is direct and powerful, “like it’s by a man.” I hope they stop “complimenting” people this way because “direct and powerful” are not characteristics reserved only for men.

Another important quality about woodcuts is its reproductivity. I’ve met artists who studied woodcuts at school but left the medium because it looks “coarse and cheap”. But for me, every piece of woodcut is a mold for flyers; it’s a publication. If I print a piece on a shirt, it’s a wearable publication, and I am a publisher. So I always have the bookstore in me

.Beimeng: A lot of your work is quite radical. They’re direct responses to some of the most direct conflicts in society, almost like…protest art.

Lilin: I don’t think I’m very radical or resistant. We are just creators responding to the current situation. I don’t deliberately want to raise my arms and shout.

Beimeng: But I find your work so loud, you know what I mean?

Lilin: I don’t think about it that way. I don’t consider myself a brave person. If there are works that are not allowed to be sold, then I don’t sell them. If the authority wants me to remove my work, I will also remove it. When I’m angry, I simply need to react.

I call myself a feminist, but I don’t think I am a feminist from a theoretical perspective. I react to topics that are very close to our everyday experience, such as menstruation and masturbation. They need to be talked about. I have a female friend who is married. When we talked about using a vibrator. She said using a vibrator seemed like cheating. I also met a woman who brought her daughter to buy a vibrator. This is why I say, “let a woman’s first 100 orgasms come by herself.” I even go as far as to think that if women do not fully explore their body, the first sexual experience should be considered rape. Because we do not feel the sexual pleasure, right? That’s why I get angry.

Beimeng: My god.

Lilin: So I think I cut the ground from under the patriarchy's feet. A lot of men were quite uncomfortable seeing the slogans I came up with. Next, I might work on something related to menopause, because I don’t think people care enough about what change of hormones can do to women. As someone who enjoys masturbation very much, I’m worried that I will enjoy it less and less in the future. That’s why I say, “One is never too old to masturbate.”

Beimeng: And I have a question for you from Charlotte. Woodcut prints have been around as a way to express political ideas (and even propaganda) since the 1930s and 1940s, exemplified by Lu Xun's new woodcut movement. In the early days of the PRC’s founding and during the Cultural Revolution, woodcut prints were extensively used for propaganda art. How do you see this medium’s historical role in political dissemination and using this more traditional form of art to spread new political ideas?

Lilin: I did see some of Lu Xun’s woodcut prints. While I do like some of them, there are others that I reject. I don’t like those with strong slogans. With my work, I think it’s still a form of personal expression, and I like to work with others together. The purpose of organizing workshops is to inspire people to talk about their own situations openly. We are actually just all learning to speak out.

Actually, one woodcut master I really like is Mexican artist José Guadalupe Posada. He really influenced my artistic approach, and I incorporate many elements from his art. He is a printmaker who created numerous works for the news media. The calavera, a representation of the human skull, is a prominent motif in his work. I also have a fondness for Jiama, which are religious woodcut prints made by people in Yunnan province. The works have a touch of divinity in them. People would pray to a deity before carving the artwork, and after completion, the pieces would be burned. I really appreciate this craft-ey spirit, where it's less about creating long-lasting art and more about its utilitarian purpose. They’re meant to be used and discarded.

Beimeng: Can we go back to what you mean when you say “speaking out?” I take it as you voicing a political opinion about a public issue.

Lilin: Yes, but I think “speaking out” covers a broader range. I think political expression is just one kind of expression, one I don’t want to get stuck within. Or else it will be like chasing after a fist, it will be very painful. I need to feel that I’m enjoying it, that I’m responding to all sorts of conversations. This all counts as speaking out.

Recently, I’m reprinting a series about forgotten women in Chinese history, and I want to make a small zine. He Yinzhen for example, was a fascinating woman. Do you know that she was the first known anarcho-feminist in China?

Beimeng: I didn't. The last time I was here, I took a photo. Then I researched online yesterday to find out about her story.

Lilin: That’s the purpose of these prints, to spread awareness. I felt that there were too few women recorded in history while making the series. I wanted to unearth more of them. When He’s husband, a noted scholar, passed away, her story was soon forgotten. But she was an early feminist in China, whose thoughts can be regarded as radical even to this day. Her powerful essay, "On The Revenge Of Women” (published in 1907), challenged the conversation around gender at the time as limited, as something just within the male imagination. Real feminism recognizes global, systematic oppression of female rights, it’s not something that can be undone just by liberating one woman, you know. That is my very rough interpretation. All I could find about He Yinzhen is a side shot in a group portrait, so I decided to make a woodcut dedicated to her.

Beimeng: You said that your current projects are not as grand in scale as your previous endeavors. But if your work were to be shared freely, its potential would be enormous. By limiting it to a small circle, its social impact is inevitably limited.

Lilin: Right. My friends and I are a little bit wary of the media. I’d prefer sitting down with just 10 people and having a good conversation, rather than having the media briefly flash my work to 10,000 people. When each of us personally shares these ideas with others and nurtures those connections, it becomes a living, growing relationship that holds more significance.

Bio: Han Lilin, Dalian➡️Shanghai(…➡️Hong Kong), feminist, woodcut artisan. She enjoys making woodcuts, cutting papers, playing with clay - all kinds of simple media, with friends’ company.

Who we are:

Beimeng Fu is a video journalist based in Shanghai. She is a lover of languages and documentaries.

Ye Charlotte Ming is a journalist and visual editor covering stories about culture, history, and identity, and her hometown’s German colonial past.

Yan Cong is formerly a photojournalist currently pursuing a research MA in new media and digital culture in Amsterdam.

Interviewer: Beimeng Fu; Translator/Editor: Ye Charlotte Ming, Beimeng Fu; Copy editor: Krish Raghav

If you like this post, please share it with others and consider becoming a paying member.

If you’d like to make a one-time donation, click here: