Chen Ronghui: Art might be better at revealing the truth than news

In Issue #6, we speak to the Chinese photographer about transitioning from journalism to art and being an Asian artist in the U.S.

Hi there,

Hope your new year is off to a great start!

We are delighted that Far & Near was featured by Substack in December. We talked about how we started the newsletter and what we hope our readers will get out of it. Read the story here.

In this issue, we interviewed Chen Ronghui, a photographer based between New York and Hangzhou. If you like this newsletter, please consider becoming a paid subscriber and help us spread the word.

For the Lunar New Year, we are also giving a 20% discount on yearly subscriptions.

Chen Ronghui is a photographer from Lishui, a city in the southwest of Zhejiang province. He has won numerous awards including the World Press Photo, the BarTur Photo Award, and the Three Shadows Photography Award. His photobook, “Freezing Land”, captures the fate of young people in northeastern China’s shrinking cities. He was the visual director at the English-language news site Sixth Tone before going on to pursue an MFA in photography at Yale School of Art in 2019.

In this interview, we discussed his transformation from photojournalist to artist, being a Chinese artist in America and identity politics in photography, and the works he’s created since Yale. The interview has been edited for clarity and brevity.

Charlotte: Tell us why you left your photojournalism career to go to art school?

Ronghui: I started working in photojournalism after graduating from college in 2011. All in all, I spent almost 10 years in the news industry, with experience in various types of media such as the print newspaper Urban Express in Hangzhou, digital media The Paper in Shanghai, and finally Sixth Tone.

I realized that, although I was a dedicated photojournalist, I love photography more than journalism. In the current times, art might be better at revealing the truth than news. In China, we have more censorship. But whether it is the New York Times or The Paper, each newspaper has its own editorial agenda, which carries some biases and “stereotypes”. As a photojournalist, you must produce images that cater to the style of the media you work for.

And of course, after working for several years, I now have some savings to support myself to realize my dreams.

Charlotte: What are some of your takeaways from Yale’s photography program? How are you approaching your photography practices differently now?

Ronghui: I still use documentary photography to tell stories about the era we live in, but it’s more about exploring my personal experiences and feelings, in the hope that other individuals or groups can relate.

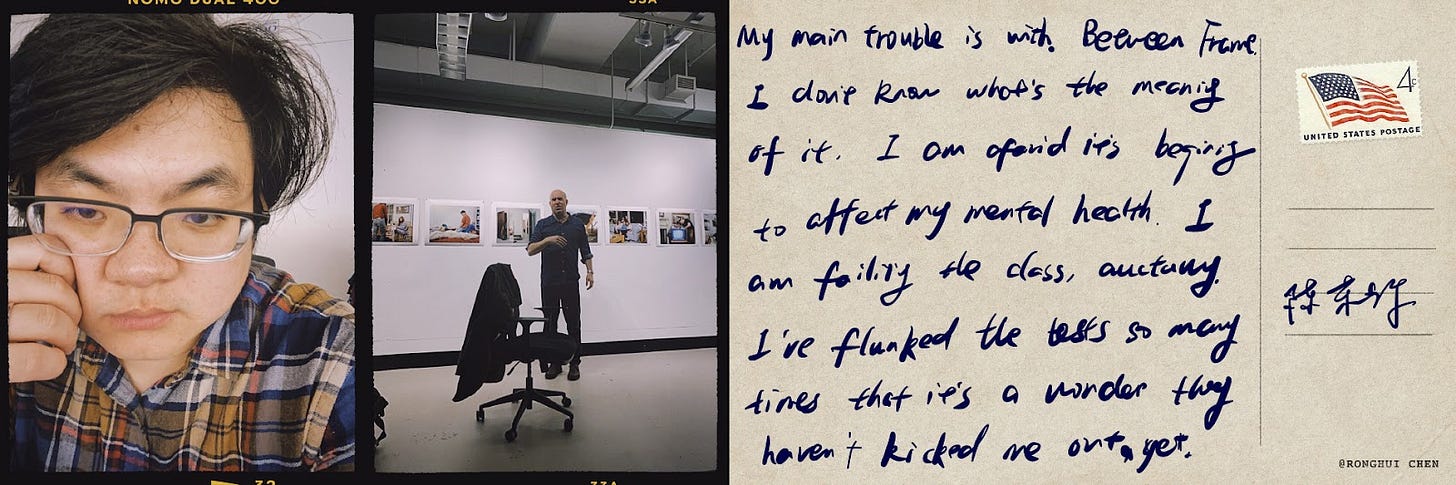

Like my project “Postcards from America”, which is a conversation between myself and Yung Wing, the first Chinese student to graduate from a U.S. college in 1854. What it reveals is that the circumstances of Chinese students in America haven't changed much in the past century. It’s also a microcosm of what Asian Americans have encountered in the U.S.

When I’m creating art, I’m free from restraints and open to visual experiments, like incorporating collage and other languages. I think the most important thing here is sincerity. Analyze the inner self, try to touch and understand it with artistic techniques.

Charlotte: You penned an article about ethnic Chinese photographers in the U.S. being pigeonholed into a stereotypical idea of what their work should be like. More specifically, their works often have to have something to do with identity and their (nude) bodies to be recognized by the mainstream photography industry. My feeling is that this type of work is often framed in the western media as a rebellion against the conservative and totalitarian state. What do you think about this?

Ronghui: I won’t directly criticize the artists who make these works, because after all, some artists, like Patty Chang and Tseng Kwong Chi, are really interested in the topic of body and gender and have explored this very well. The core issue is still — what problems do Chinese artists want to solve? What problems are we facing? I don’t have any specific answer. But I think our work should focus on society. Body and gender are just two of the issues we need to work on, but they are somehow regarded as mainstream by the western academic and curatorial system. It’s very narrow.

I have carefully studied the history of those Chinese artists in the 1980s and the process of how they became accepted by the western art museum system. What the art museums really care about is politics, not artistry, although art and politics are closely tied to each other.

Upon MoMA’s reopening in fall 2019, there was a gallery dedicated to Chinese contemporary artists, with the exhibition titled "Before and After Tiananmen" (read curator Xin Wang’s critique here). Is 1989 really the most important year for Chinese contemporary art? Those who are familiar with it actually know that the pivotal moment in Chinese contemporary art history came before that.

As I wrote in my article, this trend of creating work with the body didn’t start with Asian American artists, but with African American artists. When mainstream Western societies pay attention to minority groups, novelty-seeking comes first and foremost. Whether there will be a deeper interpretation is doubtful. The art market also accelerated it. We can certainly consider it a good thing for minorities to get attention, but we must always be vigilant. Prejudiced attention will only harm the minorities in the end.

My latest project, “19 ways of looking at Wang Wei”, explores how a Tang poem was translated into different English versions, and how the misreadings in them try to combine scattered perspectives used in Chinese painting and photography.

Being “East Asian” doesn’t just mean having a different body and face, it can also mean having a different perspective.

Charlotte: I remember when you first began studying at Yale, you said you felt a strong sense of alienation as a foreigner and as a foreign photographer. How do you feel now after two years?

Ronghui: I had never studied or lived in the U.S. before becoming an international student at Yale. Everything here was new, and I spent some time getting used to it. But I continued to work on my projects without having to ask what Americans or my American classmates think of them.

I feel that we as foreign artists don’t need to pay too much attention to what the mainstream thinks we should do because our work is easily misunderstood anyway. Robert Frank, who represents the best of American photography, was an immigrant. But he was a white European. If he were black or Asian, would he be so readily accepted as the best of America? Why could Frank travel around the U.S. to photograph around that time? Did he know the country when he first arrived?

Through the education I received today, I think I may know the U.S. better than Frank did. So in a way, self-confidence is more important.

Charlotte: I’d love to talk a bit more about the “Meyer Lemon” project. How did you come to develop it? You also used three different approaches to iterate the story. What’s the thinking behind each part, and how do the three parts correlate with each other?

Ronghui: In the first chapter, I wanted to present the state, color, luster, etc. of the lemons in as many ways as possible, and to repeatedly photograph these lemons alongside everyday objects. When looking at these boring objects of modern life and observing these deteriorating lemons, they in fact embody consumerism in modern society.

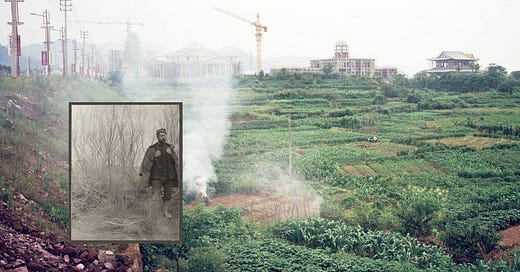

The second chapter is a visual collage I made after going through a large number of archives about Frank Nicholas Meyer. As a plant hunter at that time, he needed to take photographs as evidence of his achievements. So his self-portraits became very good documentation of China at that time. In combining his photos with my Chinese landscape photography taken more than 100 years apart, I was hoping to evoke a visual dialogue across time and space.

I created the third chapter in the U.S. after a trip to China in February 2021. I began to imitate Meyer's gestures and pose by species of plants imported from China that I found outdoors in the U.S. The clothes and shoes I wore were of American brands manufactured in China, a continuation of the story of globalization.

On the one hand, I admire Meyer very much as a plant hunter. He explored tirelessly and documented his journey with photography. The process of his exploration is very much like a photographer's creative process; wandering around. On the other hand, he obviously had greater privileges living in China as an American at that time than myself living in the U.S. as a student today.

Charlotte: Given your background as a photojournalist, are you ever afraid that the overly-theoretical approach to photography makes it harder for your work to resonate with the general public?

Ronghui: I think some journalistic habits, such as critical thinking, are still very important in creating art. The two processes are very similar in nature. They both aim at ‘extracting’ truth from life. The difference is that news cannot be staged, but art can.

The function of news photography has always been very straightforward, and now it can be replaced by videos very easily, especially in breaking news or feature stories. Now the majority of news is distributed through social media, and information is compressed and fragmented. Ordinary people can no longer reach the “truth” through this type of photography. But perhaps because art is not as “public”, we may have a better chance of telling the truth.

Unlike in my days working as a journalist, the comments and views are not necessarily my concern now, as long as I’m being honest with myself and have no reservations. I prioritize my self-expression. If people who are interested in my work see it, that will be enough.

Charlotte: Who and what inspire you?

Ronghui: I get inspiration and encouragement from the works of the photographers, film directors, and writers I like. For example, photographers like Walker Evans, August Sander, Jeff Wall, Philip-Lorca diCorcia, directors such as Edward Yang, Jia Zhangke, and Andrei Tarkovsky, and novelists like Gabriel García Márquez, Leo Tolstoy, Yiyun Li, and Xiao Hong.

In a conversation between Jeff Wall and Gregory Crewdson, the head of the photography department at Yale, Wall shared some advice: “Relentlessly study the best artists and do nothing else.” It’s uncommon to hear such old-school advice today. Carrying on tradition in art is very important. No style or genre comes out of nowhere.

Charlotte: What are you working on now?

Ronghui: I'm on a road trip for a project about shrinking cities in the U.S. that I have been meaning to do. I set off from New York in December and visited Rochester, Buffalo, Niagara, Pittsburgh, Detroit, and Youngston—typical American shrinking cities. After the first round of shoots, I will start editing and see how to develop the story.

I realized that I’m not into the so-called “aesthetics of ruins” and try to avoid shooting such scenes because they have been captured repeatedly, to the point of stereotyping. In “Freezing Land”, rather than focusing on the elderly people (who were left behind), I chose to tell the stories of the youth.

When I started thinking about doing a U.S. version of “Freezing Land”, I had a sense that I might be more interested in the death of urbanization, an illusion of the past and the present being blended.

I was supposed to fly back to Shanghai on Jan. 3. but my flight was canceled because of COVID. More than 20 flights have been canceled between China and the U.S. (at the time of writing). I didn’t expect globalization would be so easily disrupted. With that said, I’m a big believer in global connectivity. The pandemic will pass, and we’ll be able to hug and trust in each other again.

By the time of publication of this Q&A, Chen Ronghui did manage to get on a flight back to China.

Who we are:

Yan Cong is taking a break from photojournalism and pursuing a research MA in new media and digital culture in Amsterdam.

Beimeng Fu is a video journalist in Shanghai. She is a lover of language and documentaries.

Ye Charlotte Ming is a journalist and photo editor covering stories about culture, history, and identity. She’s based in Berlin and working on a book about her hometown’s German colonial past.

Interviewer: Ye Charlotte Ming; Translator: Beimeng Fu and Yan Cong; Copy Editor: Sarah Magill

Have a comment or just want to say hello? Drop us a line at yuanjinpj@gmail.com

Liked our content? Become a paid subscriber of Far & Near and forward it to a friend!

曾经在JustPod的办公室见过陈荣辉本人,一个看起来不修边幅的身材有些胖的男人,直到杨一跟我介绍才知道他是荷赛奖的得主。顺便推荐去现场的第10集节目。